So, in my last post we quickly saw the story of the Selk’nam or Ona people, their (speculated) origins, interaction with the outside world, the genocide perpetrated against them and, in a more positive note, how they’re currently fighting to reclaim a spot in history for their culture. But, what did they actually believe in? What was their religion, idea of the supernatural and the like? Let’s take a quick glance.

To the left, a Tehuelche (aka Patagonian) native woman. As we stated in the previous entry, the tehuelche are believed to share a common ancestry with Selk’nam peoples. Their language is vaguely similar (not enough to be mutually intelligible, however)

The Selk’nam acquired their world vision and beliefs from both them and the Haush they displaced while moving towards the south, around the XIV century.

About their storytelling

For starters, all their beliefs came from oral tradition and all we know comes from their remaining members by the beginning of the XX century. Martin Gusinde, a Polish ethnologist and missionary, managed to compile hundreds of their stories, folklore, customs and beliefs before the Selk’nams became accultured by following christian missions. Cheers to that!

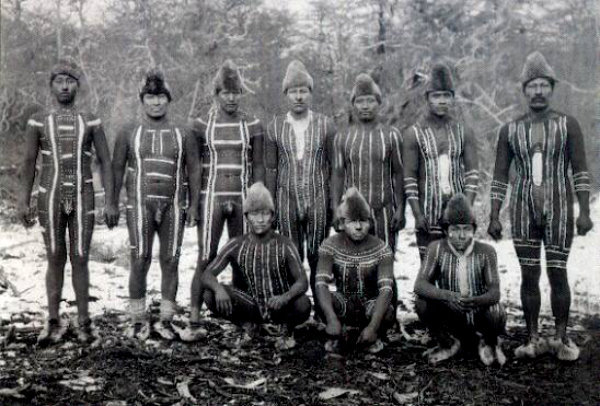

Most of the stories and mythos was passed down by the male elders of each village to the children, an adulthood initiation ritual known as H’ain, who recalled all that knowledge for decades. Their society was, like most, very divisive in gender roles1, and women never took any initiative in such matters, being instructed to remain quiet while the (male) elders taught the kids.

It appears, however, that things got to change over time. Lola Kiepja, one of the last fully blooded Selk’nam alive, compiled all the chants she remembered so they would be preserved forever. I would like to explore their gender asymmetry, since at the end of the day it’s one more aspect of their culture (and women didn’t just sit there doing nothing, they also had roles in their rites), but that’s for another post.

To the right, Selk’nam dancers dress up a male teenager to partake in the H’ain. Children 14 to 18 years old were supposed to become adults in this ceremony, and had to go through different trials, while the elders passed on their knowledge.

It was a common practice to add bits of one’s own experiences and life sprinkled here and there, which made very difficult to reconstruct them after a few generations, specially so since they lacked a writing script. Think of a broken telephone experiment, at a far slower pace, a process very common even in cultures that DO have written scriptures.

The cosmology and supreme beings

The Selk’nam revered the skies (Sho’on) as the home of many legendary creatures. They divided them by 4, one for each cardinal direction. Such skies were considered infinite and eternal, which makes sense, since the sky was the biggest and most omnipresent body known (and even then, it’s very interesting that they were aware of the idea of ”infinity” as a neverending space!)

Eduardo Hernandez from Chile

The aforementioned skies were:

- Kamuk (northern): Asociated with spring and summer

- Kéikruk (southern): Asociated with the winter

- Kenékik (western): Asociated with the autumm

- Wintek (eastern): The most important of them all

Wintek is a whole beast on it’s own. This sky was considered the one that spawned all the others. While the other three have seasons linked to them, Wintek encompassed them all, and in turn, time itself, as all the cyclical, time-bound stations already belonged to it. Temáukel, the supreme and most powerful god, resided here (we talk about him here).

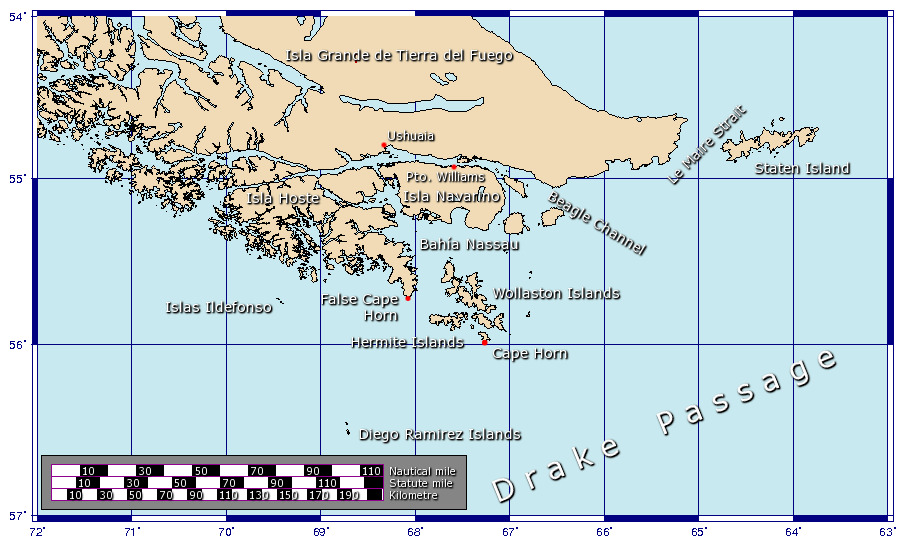

Like some other religions, the Selk’nam gave a physical location to the their sacred place, (the Wintek), which they put somewhere beyond the Staten Island, the easternmost territory in their coordinates.

The creation mythos

The Selk’nam were neither animists nor exactly polytheists. They were Henotheists, which means that they believed in many diferent supernatural beings, among which one, the actual god, was truly supreme and of unmatched power and wisdom (the aforementioned Temáukel). As a curious fact, a native Selk’man once told to Martin Gusinde (the previously mentioned missionary) they saw Temáukel in a quite similar light than Christians saw God: an uncontested omnipotent ruler, regardless of the mighty beings surrounding him. In this article, however, we’ll just cover the world’s origin according to the Selk’nam, so we can reach an understanding of the lands he ruled when we eventually talk about his nature in-depth.

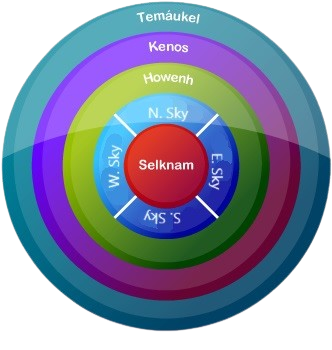

The Selk’nam believed in spirits that controlled the rules of their world. From what I gather, the most ancient a spirit was, the more powerful and legendary they considered it, to the point that the oldest of them all were considered true forces of nature and drivers of earthly change (again, all of them still wary of Temáukel and of Kenos to a lesser degree). The oldest of the humans and former mortals, eventually could become Howenhs themselves.

At least until something happened… but we’ll talk about that later.

To the left, an image (edited and translated, originally from the folklore related, Chilean website pueblosoriginarios.com), depicting the world hierarchy of the Selk’nam cosmovision.

The old spirits were known as the Howenh, and the first inhabitants of what the Selk’nam refer as the ”primitive earth” (fun fact, the Howenh were so important that the Selk’nam language had an extra verbal tense for events that happened in their times, the mythical past, set well beyond the time of the regular humans).

The most important one descended from Wintek, and was named Kenos. He’s considered as the closest one to godhood (and according to most sources, the only son of Temáukel). Despite his incredible powers and feats, and being the direct descendant of Temáukel, he’s still called a Howenh, and his father is undoubtedly the one and only God. His purpose was to organize the earth to make it livable. He arrived by climbing down a long string, that was cut when he set foot, trapping him on the plains of Patagonia (the Karukinká). To the left, a photo of the contemporary Karukinká park, named after the Selknam Mythos.

The earth Kenos found was all chaos and disorder, everything mixed and trapped in a constant cycle of disrepair and destruction. The sea (ko’oh) washed away everything on it’s path, and that’s why Kenos raised mountains and many geographical heights to placate them (Possibly the Andes mountain range, most likely, at the westernmost point of their land, and also the most remote from the Wintek. The Selk’nam didn’t live there as they had no boats to get past Tierra de Fuego, but they had contact with Kawesqar people, whose culture reached that zone).

He quickly realized, he needed others to fulfill some of the roles of the Earth, since he wouldn’t just stay there forever doing everything (it seems even the Selk’nam knew micromanaging can be the most tiresome thing…). And that’s why he created the first of the Howenh, similar to him, yet different in purpose and power.

The first one was Kranakhátaix, the old sun. Little is known about him, and usually is only mentioned as the proper ancestor of who would eventually become the current sun, Kren from the Kenékik sky. Kranakhátaix was an elderly spirit who shed immense light to the sky, making the days far longer and brighter. Later on, after everything was created and Kenos mission ended, his son, Kren would replace him and properly balance the daytime2, along with his wife, Kre (the moon), who was born at Kéikruk sky. Kre would shed a faint light before and after her husband, during the dawn and the dusk. They both also had a daughter called Tamtam. The whole family ended in terrible terms after a tragic incident, but that’s another story (that can be read here).

The Selk’nam seems to diffuse the criteria for a Howenh. While they’re regarded as humanity mythical ancestors, we can see many of them weren’t related to humans at all. Howenh could be (and that’s my educated guess) an umbrella term for many forces and pieces of nature, both originally created by Kenos, and also old ancestors of humans that eventually got old and powerful enough to join them in the ranks. We’ll get into that soon.

In the meantime, Kenos also lifted the skies up, so they made room for trees to grow.

All of this was made in a single day, leaving Kenos tired and idling by the evening. Then, distracted, he mindlessly squeezed the water out of some soil from a swamp, and made two pieces of genitalia (male, sees and female, asken), leaving them aside. Right after he went to sleep, both started copulating, and from them… the first Selk’nam came to life!

Going back to the mythos, the process repeated for many days, and eventually, thousands of Selk’nams lived. Kenos gave them different territories and split them among them, so they could find food and shelter, which explains the 3 diferent factions among them that existed by the XIX century, each located in a different spaces inside the Land of Fire, and at a semi-constant conflict-harmony dynamics with the other two. Their religion stated those lands belonged only to them, and no one couldn’t kick them away (If only that actually came to be the reality…).

Kenos got bored eventually, and made the humans capable of speech, he gifted them the ability to craft a language. The Selk’nam learnt quickly, and would never again stop talking (and their language is still spoken as of now!).

Now that they could talk to him, he also gave them the gender roles, taught them how to have children on their own (instead of relying on the clumps of clay to keep having them on their behalf), and also taught them morals (treating elders with care and passing down traditions and wisdom to children, among many others).

That second part of his mission took him many years, and by the time he was finished, he fell asleep, now a very old man. He waited for death, but it didn’t come, and eventually woke up. He left the humans, then, to chase death by himself, accompanied by other elders, the most wise of them all.

They traveled north, to unknown lands (probably at some point north of the Tehuelche, the farthest fellow civilization they probably were aware of and also their actual ancestors), until they fell, exhausted. Wrapping themselves in guanaco skins (some kind of wild llamas), they finally found death. But not for long!

During their final rest, their bodies regained their youth, and ascended into the cosmos itself. Kenos finally got back to the skies, this time bringing with him the first and oldest humans. They became the stars above the Patagonia, Kenos being the one known as Aldebarán, shining fiercely. (To the right, a photo of the Taurus constellation, whom Aldebaran and other starts belong to).

As a little detour, interestingly enough a Selk’nam told a missionary that during his journey, Kenos also made a couple genitals up there, but this time with sand. Those would eventually become the white men (the only other race they were aware of, meeting them in the XVI century CE for the first time). It’s quite interesting because that’s direct proof of their antique legends evolving in recent times, adding to their explanations events (meeting the white man) that happened AFTER the original story was created.

During this period, death was transitory, and by Kenos decree, many could rejuvenate as many times as they wanted, and when they didn’t want to anymore, they would get turned into landscape elements (hills, rivers…) or into other howenh (many of them were formerly humans, as we stated before). Hell and other aspects of the afterlife wouldn’t come to be until later.

Later on, death would become permanent, due to machinations of other Howenh. Those would spark rivalry and discord among them, which would be object of many tales. The Howenh would then shed their mortal, human properties and become true aspects and forces of nature, as they weren’t bound to mortality anymore. But that’s matter for another story.

I would love to keep going, but unfortunately this article is already becoming too long and I feel that every paragraph leaves out so much. Next time, we’ll keep going over mythology, and explore many other ancient beings, Temáukel himself, and other ones, maybe remaining myths here and there, too. Until then!

Sources I consulted:3

- Gallardo R. C. (1910). Los Onas. Cabaut & Cia.

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/selknam/kenos.html

- https://www.patagonie-voyage.com/blog/peuple-Selknam.php

- https://selknamstudy.blogspot.com/

- Read more about their societal and gender roles clicking here ↩︎

- Or more precisely, he would be visited by Kwányip, a mighty Howenh, and would force him to adjust the brightness and keep the days and nights balanced, since Kren was not as powerful as his father. ↩︎

- On top of the one from the previous, related article(s) ↩︎

Post your thoughts!