In the previous articles regarding Selk’nam peoples, we explored a -somewhat rushed- summary of their past and major contacts with the world, and then the basics of their mythology, and we even dropped the name of their most important god, Temáukel, along with the mythical ancestors or Howenh. Let’s talk about them with a little more detail!

Temáukel: The supreme being

Temáukel is the name the Selk’nam gave to the being they revered the most, and even feared to some degree. He’s also the ruler of the Haush pantheon. No Selk’nam managed to properly describe him; he’s supposed to have no body (yet still is refered as Kenos father, implying he’s of masculine gender), and lives very detached of mankind and the earthly world in general.

An interesting thing about Temáukel are the dynamics between his figure and the Selk’nam: Temáukel is called the force of life, an organizing power of sorts. At the same time, he’s stated to be passive and totally indifferent to humanity pleads and needs. That’s why he, as we reviewed in the previous entry, created Kenos and sent him to the world below instead of fixing it himself.

At a glance, we could conclude that Temáukel is what the anthropologists call a Deus otiosus, a being that just stays on the sidelines and does not intervene at any point, no matter what’s the situation on earth. But, at the same time, the Selk’nam had complex ceremonies in his honor, lest he would become angry for any given reason, and send death, illness and disruption to the lands the tribesmen inhabited. So, deep down they believed Temáukel was willing to step in only if something were to irritate him.

Remember the Selk’nam costumes we also saw in the first entry? They painted themselves as Howenh there. The Selk’nam made costumes of many mythical beings they adored, but that wasn’t the case for Temáukel. Not only he didn’t have a body to represent, but probably the taboo of trying to portray him was also too great to even try. The fear of bothering Temáukel was so great, that they even refrained from uttering his name out loud except in very specific contexts.

Speaking of his name… it didn’t really mean anything. Unlike many Howenh, whose name meant what they were (e.g. Kreen was the name of the sun Howenh, a name that literally meant ”Sun”), Temáukel didn’t really mean anything as a word. Think about any common name, such as ”George” or ”Peter”. It was just what we would call a proper name.

It is unknown when the cult of Temáukel started exactly. Patagonian groups whom the Selk’nam split from centuries ago, already believed in him1, and so did the Haush, implying he could have been worshiped for close to a millennium, if not more.

There’s not much more regarding him, to summarize, he’s a timeless presence to whom the whole earth, inhabitants and nature forces belong. He’s stated to exist since forever, and from the day (and onward) that the last Selk’nam disappears from the face of earth, he will keep existing, since he’s eternal and unbound by this world.

We are but an insignificant blip within the eternity to him

The Howenh

As we stated, the Howenh are sacred ancestors and current forces of nature that have roles assigned by Kenos (obeying the Temaukel’s command). They’re mighty and almost eternal; even if they eventually die and transform into aspects of nature, much like Kenos did by becoming a celestial body, their soul never leaves their new body, observing their surroundings for as long as they continue existing. There’s dozens of Howenh, so we’ll have to focus on the most important ones. Maybe in following entries, we can include those that we don’t dissect here.

Kenos

There’s not much more we can say about Kenos as a godlike being, that wasn’t explained in the creation mythos. He’s the second in command, the closest one to Temáukel, and the most powerful over all the Howenh and the rest of the creatures. After his death, resurrection, and ascension to the stars, he and the elders that accompanied him remained in the nightly skies, watching over humanity. They roam the sky, reminiscing over their creation.

Čénuke

Speaking of the creation mythos, we’re reminded that even Howenhs enter a state of deep sleep, nearing death, over time and as they get older and more detached of the world. Kenos himself experienced that, managing to finally escape by ascending. That’s why, before his departure, he created the rejuvenating system, where both spirits he raised and mortals (future Howenhs) would be ”washed off their elderliness” and be made young and active again.

When he finally left to seek his own death and go back to the skies, Kenos met Čénuke in the south, who he ordered to take the rejuvenating role in his absence. Old men and fellow Howenh would either come to his bathing house to ask him to be cleaned, or, in the case of the later, he himself would visit and clean them himself (since it’s not a very good idea to leave into disrepair spirits that Kenos put there, by order of the almighty Temáukel).

To the right, a modern illustration depicting Čénuke cleaning a mortal. Made by the talented Josephine Moreno and uploaded in 2019.

Čénuke was known as a very sadistic creature, rejoicing with his abilities, and often killing humans and Howenh for fun (even though true death didn’t exist yet, so they just got stuck into a temporal lethargy until he decided to undo the affliction).

He even tried to use his vast powers to rule over all the other Howenh once Kenos left! But was fortunately stopped by their combined forces.

He would later be double crossed by the Howenh Kwányip, making eternal life sadly go the way of the dodo, which we will explain later in more detail. After that incident, though, he abandoned earth and became a star in Canis Minor constellation.

Ha’is

Ha’is is another Howenh who eventually transfigured himself into a tall mountain. Way before doing that, he had a mixed reputation, and part of his lineage is considered equally bad news. As a matter of fact, I haven’t found any photographies where the Selk’nam disguise themselves as him or his family. Could it be a sign of disdain, or not wanting anything to do with them? The entire Ha’is clan is also eventually turned into different mountains of the Patagonian landscape.

Ha’is and his kin came from the north2, and was a proficient hunter of guanacos which he tamed and brought with him from there. He then met Nakenk, a fellow Howenh, and his daughter, Hósne, whom he fell in love with (despite being married with the mostly unknown Kásmen). Their relation was secret, since Nakenk considered Ha’is vulgar, and he also noticed the later had a very elongated ”atribute”, so long that he even used it to fish. Ew!

One day, Nakenk secretly spied on them and learnt of their encounters, saying nothing to them but becoming livid. With the help of another fellow, the dangerous Caskels, he swapped Hósne with Ha’is own relative, his sister/daughter Akelwóin. Oblivious to that (but still unforgiven by many Selk’nam and turned into an object of repulsion by many other Howenh) he laid with his daughter. Like a reverse Oedipus!

They had the even more infamous Kwányip. When Ha’is learnt about the events, he became furious to Nakenk, but the later was long gone and hiding, and avoided the wrath of the tricked ancestor.

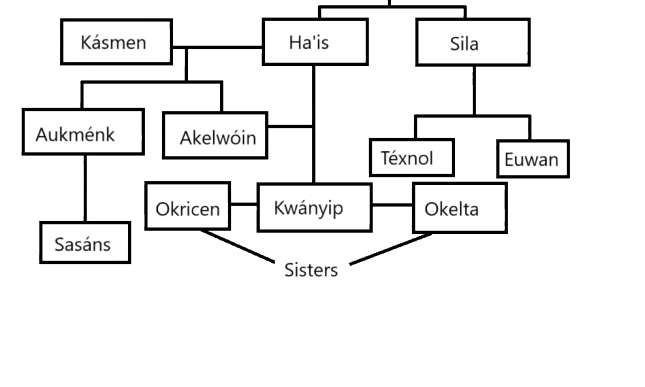

He would be treated like a pariah for the rest of his mortal lifespan. He also had a brother called Sila, who along with his children Téxnol and Euwan turned into a mountain somewhere in the past, and lastly, another son, Aukménk, who made him a grandfather by having two children with an unknown female (Howenh? human?), both called Sasán. To those who feel lost with all those names, here’s a family tree I have quickly made to summarize everything, including Kwányip’s future wives.

Kwányip

Kwányip was kind with his own family. He never got into conflict with his father, and it’s stated he was in very good terms with both his brother Aukménk and his nephews, the Sasán(s). However, he was possessive and cruel to others. After marrying Okricen, he wanted to also marry her sister Okelta, but a third brother was against it, stating Okelta was too beautiful and he loved her too much to pair her with the son of Ha’is. Furious, Kwányip turned him into the first owl, who screeched hysterically and never again got to taste the delicious guanaco meat. Okelta became furious with Kwányip for that, and the later, on top of marrying her, put a curse on her anyways, using his powers to turn her into the first bat, stating:

”You shall be black and naked, you shall have no clothes or fur (or) feathers, you shall go about at night and not in the day; people shall be afraid to see you, and if they do see you, they will get sick and die”.

He eventually managed to ascend to the skies, just like Kenos, and also became a star (along with his spouses), nowadays being Betelgeuse, in Orion constellation, Okelta and Okricen the two stars next to him. Quite a sad fate for the sisters. (A photo of the constellation to the left).

Some other variations put him as the Scorpius constellation, but that’s matter for another entry (multiple Selk’nam subgroups existed at the same time, so it’s reasonable to think that they had slight variations in their stories as they drifted apart)

Kwányip also inherited the tamed guanacos, and his family was the only one that could eat as many of them as they wanted, since the rest were wild and unwilling to cooperate, and other Howenh hardly got to hunt them.

He got into many stories (that I may or may not comment somewhere in the future), but he’s specially infamous for being the one who ended the rejuvenation cycle and eternal life -much to Čénuke’s chagrin-. Čénuke and Kwányip already had a strained relationship. He was a foreigner from the north3, son of the despised Ha’is, and he monopolized the delicious tamed guanacos for his clan. They often would engage in petty conflicts, one throwing rocks or ice to the other while the later was occupied hunting or just idling.

The tipping point would come when one day, his appreciated brother Aukmenk told him he didn’t want to live anymore, feeling tired of the neverending cycle, and having as the only alternative to become catatonic and frail until Čénuke would clean him back into his youth.

Using his strong shamanistic powers, Kwányip put every ounce of his magic into making sure his brother stayed truly dead. But, by doing so, he broke the rejuvenation system as a whole! That meant Čénuke’s would never again be able to wash the elder Howenhs and humans. And since Kenos already left to the skies, there was nothing that could be done to fix the issue. That’s why Čénuke resigned and ascended, feeling frustrated and disappointed.

After that, the mythical past ended. Now everyone was truly mortal and unable to cling to perpetual life. Once one became old and frail, only corporeal death awaited. The Howenh eventually (after a considerable amount of time) became aspects of nature (mountains, landscapes, winds, meteorologic phenomena…) or even active forces, somehow being able to remain there after their demise, and some eventually ascended and became stars, too. The age of humans started.

The Howenh didn’t become passive agents at all, however! They still interacted with humans and sometimes among themselves, but the rules of the world were mainly solidified to how they are today more or less (meaning supernatural events still happened here and there, but at a rarer occasion). The Selk’nam would ever since keep with the rituals they learnt from the Howenh and Kenos in the form of ceremonies and shamanistic practices (We will talk about those in the future).

That’s pretty much everything for today! Otherwise this article would become too bloated to keep up. Next time, we will speak about other Howenh clans and their machinations.

Sources I consulted4:

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/selknam/kwanyip.html

- Gusinde, M. (1931). El mundo espiritual de los Selk’nam, Zeitschrift Anthropos

- https://science.nasa.gov/universe/discovering-the-universe-through-the-constellation-orion/

- Under different names, for example, the northern Pampa natives called him Soychu. In their mythology, apparently the dynamic of a creator God sending his subordinate to raise the world (much like the Selk’nam Kenos did); it is a common theme, reinforcing the idea of a shared, obscured origin regarding this dynamic. On top of that, the Tehuelche themselves believed in a supreme god called Kooch (despite the very similar name, not related to Ko’oh, the powerful Selk’nam sea Howehn), that ruled supreme and detached from humans, despite the later’s fervent faith. ↩︎

- North meaning somewhere beyond the strait of Magellan, which separated Tierra de fuego (the island the Selk’nam inhabited) from the upper territories, unknown to them. ↩︎

- Rivalry between north and south is a common theme in the Patagonian territories, specially among Selk’nam and Haush ↩︎

- On top of the one(s) from the previous, related article(s) ↩︎

Post your thoughts!