A month ago or so, I read a post asking an interesting question: when has been the first time a civilization managed to count up to a million? Even though the answer was already typed, it got me wondering… how many cultures and peoples reached such a high number in their numerical script, apart of the first ones to manage it?

Before we get started, it’s important to state how much a million is, as a number. We live within an age were we casually mention figures of insane caliber; billions, trillions and so on, are commonly heard. But, let’s put the number in a vacuum. Just using some statistics to gauge it!

- If you started counting from zero to a million, and counted thrice per second, it would still take you almost four days to finish! (And it’s very likely it would take you more than that to pronounce the longer ones, such as ”346,456,546”).

- A million miles is almost nine times what the average person will walk (and run) through their entire life.

- A queue of a million people walking in front of you would take 5 uninterrupted days of strolling until the last of them cleared the way.

- A herd of a million goats of average size would roughly occupy 13,600,000 square meters (bump it to 15 to give them a little breathing room), which is biggest than LA international airport’s entire surface, buildings and airstrips included!

Well, yes, it’s still not an impossibly large number, and most of those examples are somewhat feasible. But we can see that a million still requires a lot of input, logistics and resources that most civilizations would meet only eventually, after growing so much that they had to manage resources for tenths of thousands inhabitants, at the very least.

Only a handful of peoples ever advanced so much (on their own) that they had to work with such a bloated number, let alone even higher ones! Today, we will check some of the cultures that managed to achieve the 7 digits benchmark and how they pictured it1. Off we go!

Ancient Sumer

The Sumerians were one of the oldest civilizations across all mankind, able to build the cradle of civilization located on the Fertile Crescent, and to this day, they have also the record of the oldest written script, the Cuneiform! Their writing has been around for at least 7 or 8 thousand years. Those peoples were some serious early-riser workers!

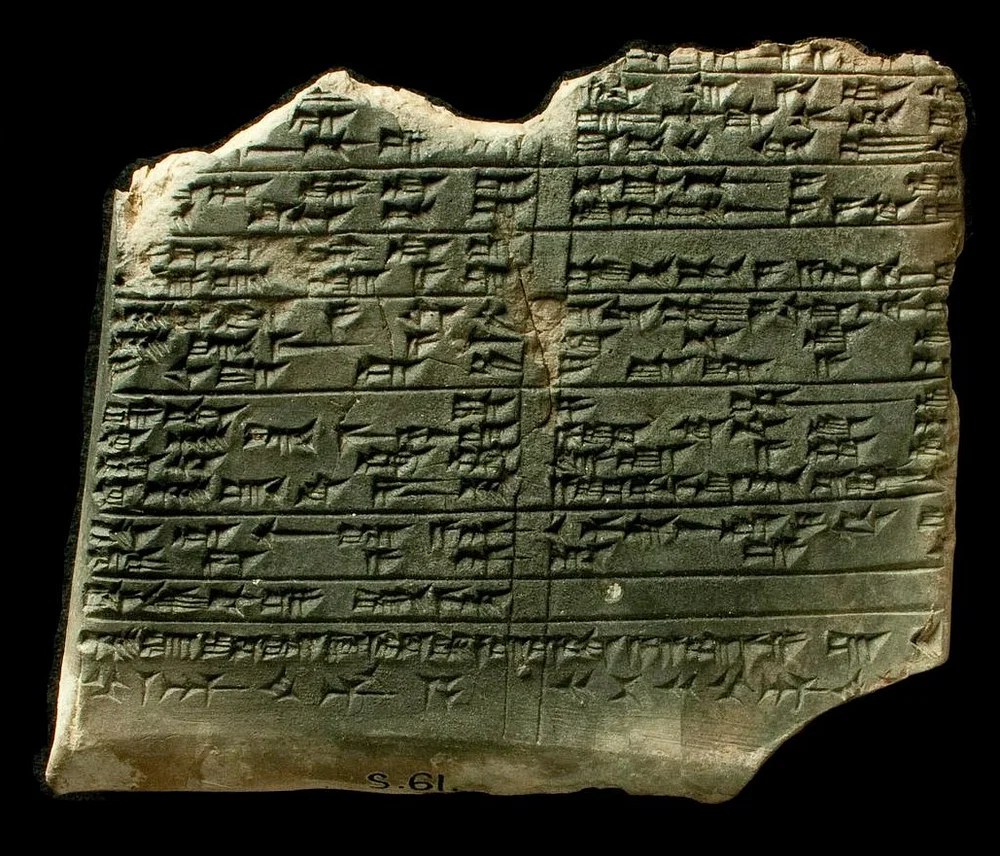

Their written script, including their number system, was made based on wedge imprints, specifically the shape they left on clay tablets and other malleable surfaces. We can see an example below, a table of proverbs from the Library of Ashurbanipal made millennia later, but still using the same method of writing.

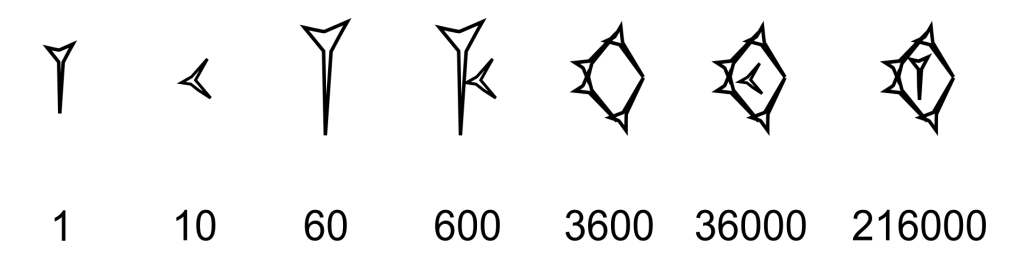

Going back to their numbers, they used a large number of counting systems, from which the most widespread was one that applied base 60 combined with a base 10, instead of just using the later, like we do. To better understand it, that means that while we add a new digit every time the previous one reaches 10 (after 99 comes 100, because the ”9” is now a ”10”), they did so every time the latest number reached 60. That’s how it did pan out:

While they don’t reach one million with a singular symbol, it’s important to be aware that they did operate with such large numbers, either for commercial purposes, or logistics and management of resources. They didn’t invent a unique looking number 60 times bigger than 216,000 (if they did, it’s nowhere to be found) because they didn’t need to (that would be 12,960,000).

Just by stacking the ones they already had, they could reach any magnitude they desired, no need to keep inventing new symbols. Their calculus and arithmetic (which would later inspire the Greek and the Roman civilizations) allowed them to!3 After all, to make a million they just needed so sum 5 of their 216,000, or multiply the later by nearly any amount.

So, despite not representing the ”million” per se, the Sumerians were aware of such a big number and operated with similar measures on a regular basis. The Babylonians, their spiritual successors, would keep employing the cuneiform script and further take advantage of it’s versatility.

So, to summarize, the first remarkable civilization also was the first one that touched the million number, even if outwardly it looks like they stopped a little bit before that. Off we go to the next example!

P.D: For those with an updated enough computer, it is possible to see and even type cuneiform symbols! A little bit impractical at first, but still impressive to translate ancient, long dead languages into a modern screen. If you can read the following symbols (otherwise, you’ll just see some blank squares) it means your computer is capable of handling them!

𐎧𐎤𐎫𐎫𐎮, 𐎧𐎠𐎵𐎤 𐎠 𐎦𐎮𐎮𐎣 𐎣𐎠𐏀!

Try to find out what does the word above mean by looking up an online translator!

Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians! Another very antique culture that I would like to talk about at some point, but today we’re just focusing on numbers. Their system was almost as old as the Sumerian, dating from the third to the first millennia BCE.

Egypt was more straightforward than Ancient Sumer representing our valued number, since they, like us, used a base 10 system. A lot of cultures did so, as a matter of fact, across all the world. The most common explanation is that we have, well, 10 fingers, that we used to count in the most simple way before the written recounts existed, and that bled onto them.

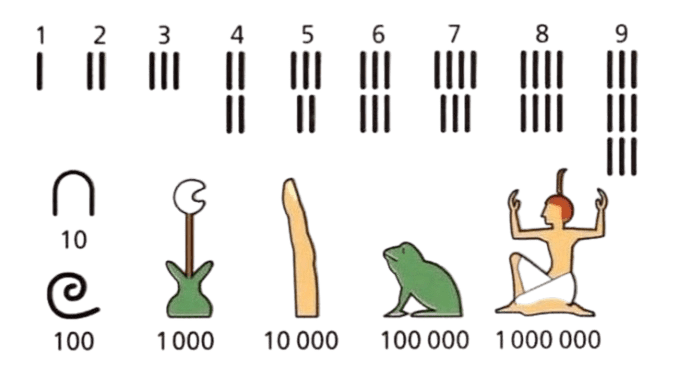

Returning to the Egyptian numerals, they were quite cute looking, becoming more complex the higher they scored. The symbols were the following ones:

The system was a little bit more cumbersome than the Sumerian, and judging the sources I checked, even the multiplication method was a little bit impractical4, and there’s no evidence that they knew about decimals, unlike the Sumerians. But hey, they did represent a million! And the base 10 is far more convenient than any other metric. So kudos to that. They expressed the digits by repeating them as many times as the number they represented. For example, to write the number 462, they would draw 4 rope coils, followed by 6 hobbles, and finally, 2 strokes. Easy!

The million was named Huh, after an Egyptian God of the same name. It also meant ”many”, to represent it was a very large amount of something, sometimes even unquantifiable (something a million can end being for most of us, since is such a big number). Incidentally, and to further reinforce that message, Huh himself (or herself, his female counterpart being called Huhet) was the god of infinity and eternity. Not only that, but also his male form was sometimes represented as a frog headed human, a frog being the second highest digit in ancient Egypt, the number 100,000!

Egypt math prowess may have not been as great as that of the Fertile Crescent itself, but it’s clear they weren’t far below them, and their profound symbolism, represented even in their very numbers, shows us the importance they gave to the discipline.

P.D: Of course, the Egyptian language has been brought to our modern computers, too. Like the previous example, an updated enough computer should be able to show you the number 1,000,000 (also the representation of Huh) here: 𓁏. Many pages5 may show you guides to write using hieroglyphics (the name of the script system the Ancient Egyptians used).

Roman numerals

Inspired by the Etruscan (a civilization that existed north of the first Romans, that greatly influenced them), the Roman numerals quickly evolved to quantify far greater amounts than the former ones could ever dream to. As always, that’s something expected to happen when a civilization reaches a great extension and complexity, and therefore a big logistic requirement to function. And who would need that more than Romans, that conquered around half of Europe, and a great chunk of north Africa and the Middle East?

The Roman system was set in bases 5 and 10. That means the number changed when the digit reached multiples of those two numbers, instead of just 10. Their sorting system was far more approachable for us: They just assigned letters to numbers, letters that they had in their alphabet, and that most of us still use nowadays on our native tongues!

The Roman system is ancient, in it’s classic form it’s speculated it could have fully formed around the 5 century BCE, and it was used centuries after the western empire was gone (along with their modern tongue, Latin), only being displaced by our modern number system.

The list of numbers and their modern counterparts looks like this:

| Roman number | I | V | X | L | C | D | M |

| Our equivalent | 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

The rules were simple. No more than three numbers of the same type could be written at the same time. To write numbers like 4, or 40, that would require four Is and Xs respectively, they would put the next digit (5 or 50) and another one to the left, as if subtracting the bigger one (40 would be XL, 50-10). Normally numbers would be written left to right, with the bigger digit to the left and the smallest to the right (18 would be, for example, XVIII). Oh, and also, the digits of base 5 (V, L and D) couldn’t be repeated, that only applied to the base 10. Lastly, I noticed that

It’s a little bit tricky, but not as difficult as it seems. After all, even the most illiterate merchants got the hang of them. Also, most of these limitations came in afterwards, meaning at different points of the Roman Empire they didn’t need to be aware of so many rules

You may be thinking, what about a million? With this system, indeed, it’s impossible to reach 10,000, let alone a hundred times that. The biggest number you can produce is MMMCMXCIX (3,999), a very insignificant one compared to our aim. Of course, they had a method for measures beyond that.

With larger numbers, Romans used one out of many options. However, we will only focus on the ones that reach a million, for the sake of not making this article hours-long to read… They had an special symbol, the Vinculum, an overline that, when put over a number, would mean the later would be valued by times 1000. Here’s how it would look:

Applying this to numerals like M and beyond, it did reach the million! On top of that, they would also use a triple outline, adding another two left and right of a given number if they wanted to multiply it by 100,000 instead of just 1,000. In that case, it would be like this:

Needless to say, numbers raised to a million by using this system did exist and were sometimes found, even if rarely (figures above a Vinculum were not needed very often). They did also had fraction systems of similar complexity, but those are matters for a different article. We can see the Romans were even more versatile at math than we were already taught in school!

Indo-Arabic numerals

Despite how remote this double denonym may sound to your ears, you may find yourself surprised by knowing that this number system is the exact same we use nowadays! Yes, our way of putting digits together (one thousand twenty tree, for example, being 1,023), is a direct descendant of the methods created on India during the first century of Common Era.

As a matter of fact, India has quite the story with math, being major contributors to trigonometry, the idea of a number ”zero” (you may have noticed most cultures mentioned previously didn’t have any form of representing a zero at all), negative numbers, etc. The base 10 method we have inherited doesn’t have a symbol for a million per se, just 7 symbols stacked, the first being a ”1”, followed by six zeros. That simple!

And, before you may think India never got that far despite having the tools to do so, they often were VERY altisonant and prone to using very high numbers when regarding religious feats performed by the gods they revered. Those measures often reached the millions. For example, they estimated the universe to be not less than 155.52 TRILLION years old, exceeding by far our modern expectations (which located it around 13.8 billion years, year up, year down). Their God, Brahma, aged 3,110,400,000,000 times slower than a human, making his age so overwhelmingly difficult to pinpoint that I’ll leave it to the Indian mathematicians of the past. It’s very curious how, despite not following a scientific method per se, this civilization managed to handle such enormous (yet precise) magnitudes and construct their cosmogony out of them.

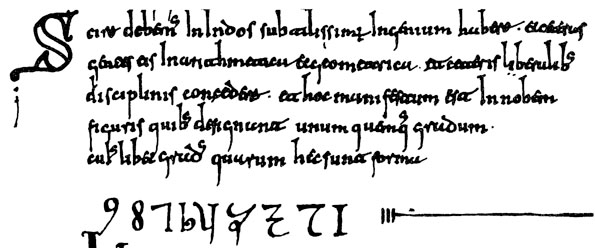

You may think this is some sort of a reach and that there is no way our system comes from such a remote place, but there’s incontestable evidence. To be a bit fairer, that system would only start resembling our own after Arabs adopted it, adapted a little bit how it worked and looked, and then exported it anywhere they went. By the 9th century they already reached part of Europe (albeit they just took part of the Spain and Portugal by then), but the system was so popular that it ended spreading to the rest of Europe during the next centuries. Efficiency beats tradition this time!

The image above consists of a small fragment of the Codex Vigilanus, a tenth century CE text from a Riojan monastery (part of the remaining Christian territories in the then Islamic peninsula) that pictures the numbers for the first time in the history of Europe. As you can see, most of them look almost the same, some changes being natural after a whole millennium of use since then.

The text acknowledges its origin, a translation I found saying ”We must know that the Indians have a very fine talent, and that other nations should concede to them in arithmetic and geometry, and the other liberal disciplines. And this is manifest in the nine figures which designate each position of each number, of which the form is [the list of numbers]”. It seems the world was more connected than we often think, the wisdom of a distant territory in Asia arriving (and being praised) even to the westernmost point of an entirely different continent.

Nowadays, there’s multiple Indian scripts that use their own versions of the numbers, many of them somewhat similar since they stem from the same place, but others having differed a lot over centuries of independent change. I recommend further research on this if you feel inclined, it’s a captivating topic and very well documented.

Maya numerals

Space is running dry, but there’s still room for one more script! The ones I always end up talking about, the Maya civilization(s)! They, on the other side of the world, also developed a system that often toyed with the millions, and even beyond that. The Maya numerals existed for a long while. Before they reached the height of their power, their spiritual ancestors, the Olmecs, already created their way of counting (or some sort of predecessor), at 3th century BCE.

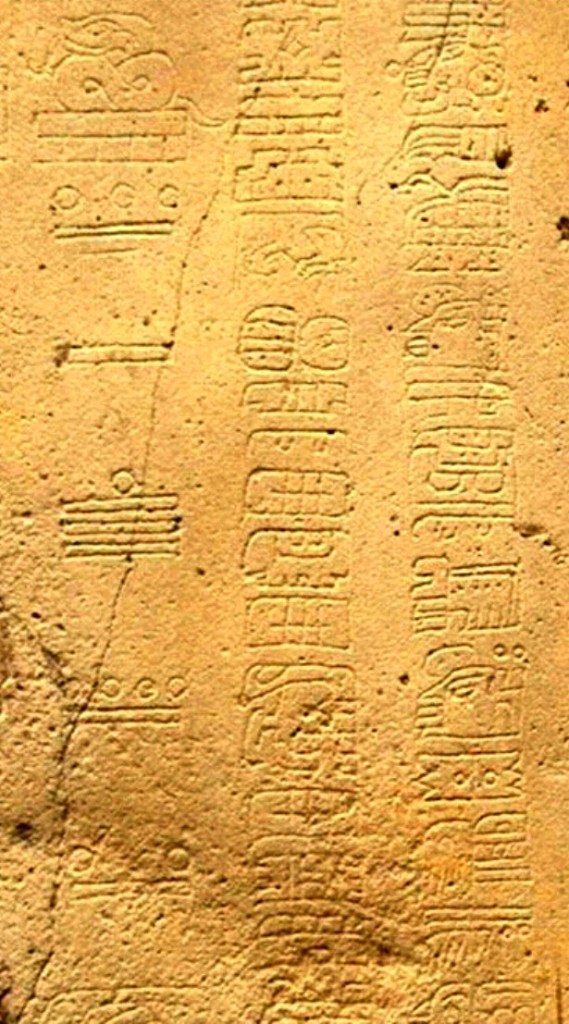

We have an example to the left. In this depiction taken6 from an Stela carved in modern Veracruz (Mexico) rudiments of a numbering system appear to the westernmost side (those bars with dots on top).

Pay attention mostly to those symbols, they’re the object of our topic and we’ll explain how they work soon enough.

It is unknown if the Olmecs did, at any point, pumped the numbers to a million, but there’s no evidence to think so. Now the Mayas, a cluster of civilizations that were heavily influenced by them, saw the potential and eventually did so, claiming the math methods and quickly turning them into their own thing.

The system is very simple. Mayas used base 20 (because there’s actually 20 fingers to count with in our body if you think about it). For numbers 1 to 4 they used dots, one per number. When they reached 5, they put a bar. Simple enough. The next 4 dots would go right above the bar, and so on. 17 would be three bars with two dots on top, for example. And then things get interesting.

For numbers like 20 and above, they would do the same think right above, BUT the number pictured above would count as 20 times greater. Let me put it with an example, the number 167 would look like this:

| Uppermost row (x20) | … _ |

| Lowermost row | .. _ |

The row above is 8 (a bar, worth 5, and three dots), and since it’s above it’s 20 times larger, so 160. Summed to the one below, it yields 167. Easy to get! They also had a modified counting system that stacked a base 360 on top of the base 20 (we have seen combining two bases is a very common thing), but that one has religious purposes and it would be confusing to cover that too, here.

When one space needed to be zero (por example, 160, that would need a zero in the block below) they used an special symbol that meant so. Which is very impressive, because very few cultures, such as them or the aforementioned India, managed to project on their own the idea of ”zero” written. The symbol looked like this:

As you can start to imagine, the numbers can get pretty immense and pretty soon, and they did! Oddly enough, the system was only polished long after the Mayas lost most of their power and entered a long decadence, the Spanish Crown arriving to the territories of Mesoamerica not much later.

Just like the Hindus, Mayas strongly linked their maths to religion and did reach very hyperbolic measures of time. A particularly long time measure they invented was the Baktun, which would translate to 394,4 years7 or 144,000 days. The Mayas pinpointed the creation of Earth to a very exact day, an specific date, to be precise. According to them, that was on August 11, 3,114 BCE, 13 Baktuns ago (at the time of writing, if you’re reading this on 2400 I’m afraid this won’t be accurate anymore), which means a total of over 1,872,000 days passed. We call their calendar (basically based on how much time passed since then) the Maya Long Count. Returning to the numbers, all of this means the mark was above a million already way before the Maya civilization was interrupted; they got a notion of a million number applied directly on their calendar!

And lastly, they had even larger measures than a Baktun, even if they were just speculated and not applied directly. They’re the Pictun (20 Baktuns), the Calabtun (20 Pictuns), the Kinchiltun (20 Calabtuns) and lastly, the Alautun (20 Kinchiltun), which would translate to the awe-inspiring quantity of 23.040.000.000 days.

As a final note, let’s see how the number million would look written in Maya.

| . _ |

| … _ _ _ |

| .. _ _ _ |

| …. _ _ |

| Blank (Zero symbol) |

For anyone curious, I have calculated the date, (that is to say, the precise point a million days exactly passed since the Long Count started), and it would be on July 13th, 376 BCE.8 As a final note, remember all the ruckus back in 2012 about the so called ”Mexican calendar rearing it’s end”? That was just that the next Baktun started, the 13th (the current one). A very memorable date for Maya peoples, but nothing earth-shattering. After all, they lived through many of those, their culture being so incredibly ancient. Our great-great-great(…)grandchildren will probably freak out, too, when they get close to the 14th Baktun in a few hundred years.

And that’s pretty much it! There’s a few systems left for another occasion, such as those invented by the Chinese, but I think a wide enough picture has been painted. Most of the ones we say had been developed independently of each other, and I think that says a lot about human ingenuity and mental capacities. We have overcome great limitations and put some great brainpower into the feat of counting and managing large quantities, and that’s something to be proud of. Mankind can get really creative when the occasion arises…

Hope you have enjoyed this article, even if it deviates a little from what we originally post about. Writing and researching all this has been really fun. Until next time!

- It’s very possible that I skip some of them, due to a mixture of lack of time and space. Maybe some day I could write a part II? ↩︎

- The image has been provided by Wikipedia, and made by the user Otfried Lieberknecht, being freely used under the license of CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons ↩︎

- https://www.mathematicsmagazine.com/Articles/TheSumerianMathematicalSystem.php ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/science/mathematics/Mathematics-in-ancient-Egypt ↩︎

- Such as https://discoveringegypt.com/egyptian-hieroglyphic-writing/egyptian-hieroglyphic-alphabet/ ↩︎

- The image has been provided by Wikipedia, the picture being taken by the user Madman2001, being freely used under the license of CC BY-SA 3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons ↩︎

- A Baktun is composed of 20 Katuns, each divided into 20 Tuns, every Tun consisting of 18 winals, the Maya months, each one being made of 20 days. ↩︎

- 6th Baktun, 18th Katun, 17th Tun, 14th Winal, 0 Kin ↩︎

Sources I consulted:

- https://www.mathematicsmagazine.com/Articles/TheSumerianMathematicalSystem.php

- https://www.worldhistory.org/article/181/ashurbanipals-collection-of-sumerian-and-babylonia/

- Robson, E. (1998). Counting in cuneiform, Published in Mathematical Association

- https://sumerian.neocities.org/nouns4

- https://www.britannica.com/science/mathematics/Mathematics-in-ancient-Egypt

- https://discoveringegypt.com/egyptian-hieroglyphic-writing/egyptian-hieroglyphic-alphabet/

- https://www.romannumerals.org/blog/which-is-the-biggest-number-in-roman-numerals-6

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Hindu%E2%80%93Arabic_numeral_system

- https://www.facsimiles.com/facsimiles/codex-albeldense

- https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/home/the-maya-and-zero

- https://maya.nmai.si.edu/calendar/maya-calendar-converter

- https://www.dcode.fr/mayan-numbers

- https://www.astrosafor.net/Huygens/2000/H22/H22Mayas.htm

Post your thoughts!