A new series I decided to start while I gather content for the other ones1, focused entirely in afterlives, hells, heavens and other planes of existence for the death that cultures from all the world ideated through the ages. In every part of this section, we will cover an specific civilization’s Underworld(s), what they consisted of, who went there and why, and what could one expect in those dreadful (or paradisiac) places.

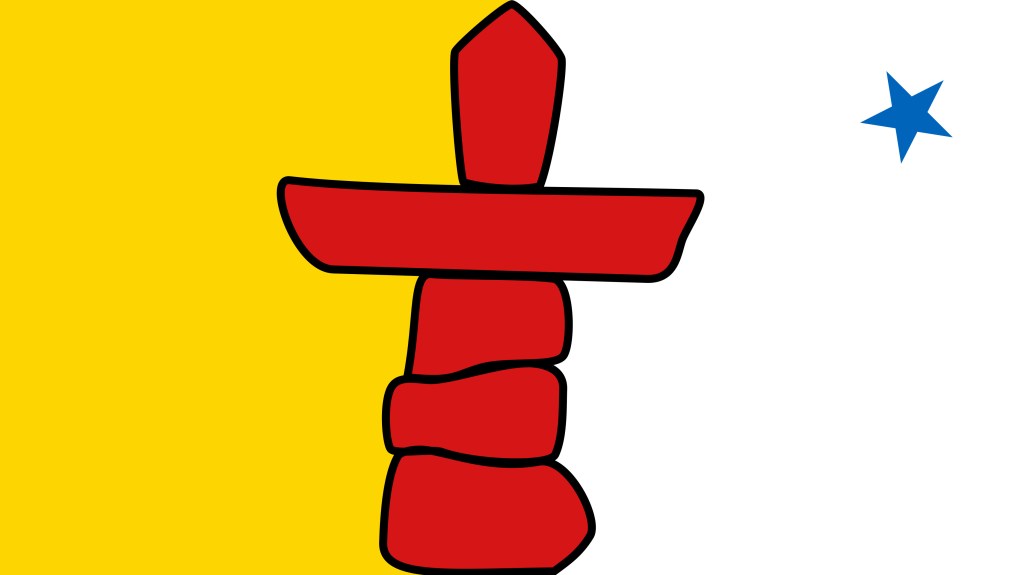

Today, we will check Qudlivun and Adlivun, the afterlife planes of the Inuit people2, a group of indigenous, similar cultures and peoples that traditionally populated the upper northern area of North America, mostly in Canada and Greenland. Some day I could write an article about their ways of living and complete beliefs, but that’s for another occasion.

Otherworldy life

As many other peoples, the Inuit believe(d)3 in the existence of an immortal soul, that exists independently of the body. After the former passes away, the later lives on, and travels to their afterlife planes. Interestingly, the Inuit also believe animal, plants and just anything alive has an eternal soul. Some groups even claim creatures are made of multiple spirits (eg, every bone is populated by an specific spiritual being)! The name they give to the soul is ”anirniq” (plural is anirniit), and we’ll name them that way for the rest of the article.

While a being is alive, the anirniq is ”trapped” or bound to the physical body, and only death may set it free. Freed anirniit would have multiple paths, involving reincarnation and/or traveling to the underworld(s) of Qudlivun and Adlivun (which we will discuss later). Until they were cleansed of their past memories and made to be able to bound themselves to a new body, however, the anirniit would still remember everything that took place during their lifetime. That posed a very serious problem the Inuit were very aware of: Every time they hunted down an animal, there was a high risk it’s anirniq would be filled with rage and vengefulness towards it’s executioners, using many ethereal powers to punish them.

The Inuit explained their unpredictable climate, randomness of their hunts (and prey), and overall unforgiving way of life as the plotting of the countless beings they had to kill in order to survive. There was some hope, however, in the fact that sticking to certain traditions and performing strictly timed rituals would more or less weaken these wrathful spirits. The Inuit had a figure called the Angakkuq4, a shamanistic figure (normally an elder) that reminded the tribe of the necessasry rituals to enforce in order to protect their kin.

There were also spirits that existed without a physical body to attach to, the tuurngait, but since those do not participate in the cycle of dying and going to the afterlife, we will not talk about them here.

Death and afterlife

When a native Inuit died, they would be wrapped in caribou skin and buried, and sometimes their corpse would be tattooed to determine which travel would the anirniq take. That, however, had no major impact as the final goal was always the same: reincarnation in a new body, either animal or human. Elders would claim death is just a ”depature from society”, as the reborn anirniq would eventually lose all ties it made in it’s life cycle. For a while, the anirniit would wander around the mortal plane, still being able to be called and talked to. This is why the period the violently killed would use to take revenge unless the rituals warded them off. After an unspecied amount of time, anirniit finally marched on to a new plane of existence: The Adlivun. The God Anguta would be the responsible of guiding the anirtniit towards there.

Adlivun

Depending of the source, Adlivun either refers to the anirniit located in the afterlife, or the place itself! In Inuit language it means literally ”below our direction”, and it’s the first place the deceased will visit, an even more merciless location than the usual icy plains the Inuit wander.5 As the name suggests, Adlivun is located below the physical world, (specifically, as Inuit recall, under a nearly bottomless ocean that sits below the earth they thread).

Though Inuit are taught to not fear death, as it is just a temporal process, most believers are very wary of Adlivun. A frozen wasteland where barely anything can thrive, anirniit usually have to cross it, so they get ”cleansed” and able to travel to the more benevolent Qudlivun. Chilling winds and snow storms make the landscape hard to distinguish, let alone navigate accurately. That’s why the Angakkuk of the tribe would teach every one else rituals, prays and give general tips to survive and get away from that underworld as soon as possible.

Adlivun is not an entirely abandoned place. Godly beings, underwater monsters of many kinds and other supernatural creatures inhabit it, the only beings able to survive in such conditions. Amongst them, Sedna is the supreme ruler of this realm. Daughter of Anguta, she is a colossal, mermaid-like called the Mistress of the Sea, filled with resentment and vengefulness since her father kicked her down to Adlivun and cut of her fingers when she tried to climb back. She lets those feelings of rage out with the anirniit, punishing them for their former bad deeds, and creting the harsh climate of this place.

Sedna lives in an immense mansion, built of stone and whale bones (in other versions, it’s a very solid and big igloo)7. The deceased ones must manage to walk through the confusing paths of ice until they eventually manage to stumble upon her house, amidst the raging winds. These paths have circular trajectories and slowly shift and drift away from the destination, so the anirniq must rely on their sense of direction and agility to move to the desired direction.

That difficult expedition is part of the necessary rites to escape. Living beings had developed through all their life sharp orientation skills, travelling through barren landscapes for hours, hunting or being hunted, memorizing complicated trails and using shortcuts and the terrain to their advantage. Managing to reach Sedna is thus a way to proclaim them worthy to continue their escape. When they finally meet her, the procedure to prepare them for the Qudlivun continues. According to custom, the Angakkuk of the living world may use their shamanistic abilities from time to time to project themselves into Adlivun and help the dead proceed whenever they get lost.

There’s different recalls about what the ”cleansing” consists of: Some Inuit claim Anguta is not the one guiding anirniit to Adlivun8, and actually lives frozen and trapped inside Sedna house, in a near-death state. The anirniit have to sleep close to his frigid body for an entire year, while praying and chanting until their mortal imperfections, misdeeds (if any) and the like are seeped (or cleaned) away. Regardless of the individual, traditionally this process takes an entire year, where the cold is extreme and almost unbearable, even for non-corporeal beings.

There’s versions stating that Sedna, while forcing everyone to stay one year with her, may be more cruel with those that deserve it the most, the anirniit that have broken a taboo, specially a very serious one. For example, at least one source9 states Sedna will punish those who commit besitality by striking their genitals for the whole year, and making it so they can’t become human ever again.

Nowadays, it’s widely thought Adlivun just awaits for those who acted wrongly during their lifetimes, but that appears to be an influence from Christianity10, to frame it as a conventional Hell. If anything, an anirniq may have to endure more or less cleansing rituals in order to pass through, but will be sent there regardless of their actions. Some Inuit seem to disagree and still claim Adlivun is not mandatory, but all of them concur that Qudlivun is a sure destination, sooner or later.

After the anirniq was finally freed of their mortal past, it was finally possible to flee and soar the skyes, right to a far more promising place, one akin to the paradise: the moon realm of Qudlivun.

Qudlivun

After the attonement of Adlivun, the dead will find a rather unusual path to follow in order to escape: A rainbow will appear, and the anirniq will be able to climb it. According to the Inuit, rainbows start at the very bottom of Adlivun, passing through it, to the living world, and all the way to Quidlivun, only to return to the former underworld after reaching their peak height (which explains their arc form). It is believed rainbows are one of the many evidences of the dead existing, and a very effective way for an Angakkuk to communicate with them.

Qudlivun is, allegedly, a place of eternal bliss and entertainment for the Inuit12. It’s the exact opposite of Adlivun, down to the name: Qudlivun means ”the ones most above us”. There’s discrepancies about where exactly Qudlivun is located. The most popular versions call it the ”Land of the moon”, and claim the celestial body is where this dreamy world exists. Others say Qudlivun encompasses the whole viewable night sky -and beyond-. Both seem to have a common origin, as in either version it’s mentioned the place is filled with holes (moon craters/stars fill this role).

No snow, ice or storms at all trouble the inhabitants of Qudlivun, and it’s always warm up there. It seems to consist of impossibly extensive plains and forests, plenty with prey to hunt that doesn’t struggle nearly as much as the earthly equivalent,13 and not much work to do at all. An enormous lake is always filled to the brim with fish. Everyone spend their time leisurely, whenever they aren’t hunting, they play, dance or just enjoy the views.

Pana is the Goddess that reigns in Qudlivun, and not much is known about her. She’s refered as ”the woman up there”, and her role is to keep the peace and enjoyment of her paradise going. The anirniq may spend as much time as they want there. Eventually, if they decide to come back, they do so on their own accord, and Pana helps them return back, at which point they let go of any memories or recalls of their mortal life, and reincarnate as any living being, be it human or animal.

There’s not much more that can be safely said about Qudlivun. Whatever else that may be written is dubious, contradicted by other Inuit or straight up has no sources backing it up whatsoever. I recommend any interested readers to check the sources I will put at the end of the article to pick any other useful information about this underworld (or would it be overworld?).

Other spaces?

There’s even less information at hand, but on top of the two previous realms, some Inuit also mention additional places, from which I gathered nearly zero information, sadly. They’re documented in Franz Boas work as Adliparmiut and Quidliparmiut. The later takes the role of Qudlivun, and the former sometimes exists as an intermediate area, or also takes the role of Adlivun. Meanwhile, they still believe in Adlivun and Quidlivun, and they’re integrated in this now five-sided cosmos. Quite confusing! To summarize it, those who claim these places to exist, state they’re distributed in this order, from highest to lowest:

- Quidliparmiut: Actual paradise, the happiest and most pleasant place to live. Everything is great up there.

- Quidlivun: Mostly wonderful place, even if not as good as Quidliparmiut. Likely a little bit colder, harsher, just enough to remember discomfort as something vague, minor, yet present.

- Adlivun: In this version, described as a cold and troublesome place, that anirniit struggle to live in. They’re able to hunt walruses, seals and other creatures, but it’s always snowy and unpleasant. Barely enough to get by. Either in this zone or in Quidlivun, the dead play with a walrus head, kicking it around. It is theorized that this is projected as the aurora borealis in the mortal world.

- Our world: Our place of existence. Where souls forget everything and reincarnate once more.

- Adliparmiut: Actual Sedna residence. An unlivable void of fiery storms and permafrost. Those who end here will suffer. In some versions, they may never even escape.

And this is pretty much the first entry! I hope you have enjoyed this brief insight to the Inuit afterlife beliefs! Next time I’ll talk about… well, any other culture that catches my eye, basically. See you then!

Sources I consulted:

- https://www.folklore.earth/culture/inuit/

- https://reader.digitalbooks.pro/content/preview/books/181680/book/OPS/Adlivun_y_Qudlivun_0004_0001.htm

- https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/blog/the-greenland-inuit-s-belief-of-soul-and-body

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inuit_religion

- Helaine, S. Rakoff. R. (2019) Death across Cultures, from the series Science Across Cultures: The History of Non Western Science. Springer Publishing, USA.

- Boas, F. (1889) The Central Eskimo. Sixth annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology, Bureau of American Ethnology.

- Cotterell, A. (1997) A dictionary of world mythology. Oxford, Oxford University Press. p. 298

- I’ll finish the other ones eventually, I promise! ↩︎

- Specifically, the way the ones located within the western side of the Davis Strait see these concepts ↩︎

- Many have recently converted to Christianity, either fully or maintaining some sort of syncretism between their ancestral religion and the later introduced one. ↩︎

- More specifically, treated as a ”spiritual healer”. ↩︎

- As we said before, certain Inuit believe the underworld journey can be altered by marking the corpse. For example, Netsilik women who are tattooed may skip the Adlivun entirely. ↩︎

- The image used for reference is a photography taken by Eli Duke. It’s freely used under CC BY-SA 2.0, and can originally be found here ↩︎

- And I recall one that said her house is indescriptible due to the thick layer of snowy winds that surround it! There are many different Inuit tribes, so it makes sense that different versions exist. ↩︎

- Instead, in these stories it’s a goddess called Pinga the one who does it,. ↩︎

- Death across Cultures, by Helaine Selin and Robert Rakoff, page 367 ↩︎

- Same source, page 368 ↩︎

- Photography taken by Rauno Träskelin. It’s freely used under CC BY-SA 4.0, and can originally be found here ↩︎

- Somewhat unrelated, but I found uout -according to Franz Boas- that those who died a violent dead, including suicide, may also jump straight to the Qudlivun. It’s oddly similar to the Maya belief that Gods are particularly grateful of those that died with violence, too, again including suicide as it’s still violence towards oneself. ↩︎

- No source states if the prey are also former anirniit. Probably not, since it would make little sense to go to the paradise to reincarnate as an easily killable animal, and then to have to go all the way back to Adlivun! ↩︎

- Picture taken by Yann Vitasse. It’s freely used under CC BY-SA 3.0, and can originally be found here ↩︎

Post your thoughts!