Note for subscribers.: Finally, a new entry regarding the Selk’nam! To those of you subscribed to our website, you may have received a message showing this article, as if already published. That seemed to be an error; an incomplete version that was sadly uploaded by accident before ending up complete. Apologies for that blunder! This is the full revised version, more thoroughly investigated. Hope you enjoy it. P.D.: I’m aware that Part III stated we would talk more about the Howenh. We will, but before that, I thought the best would be to cover this very important segment of Selk’nam world views. Without further ado, let’s get started!

In previous entries about Selk’nam culture, we discussed their origins, their creation mythos, and recalled the mythical past of some of their Howenh1. This article will be about other, very important part of their cosmology, this time related to humanity, and what’s their place amidst this vast spiritual world. We will talk about the role the average (Selk’nam) human takes in this world, and also about the shamans, or Xo’on, and what sets them apart of the rest. Let’s get started!

Common humans

It is necessary to differentiate the average Selk’nam tribesman from the Xo’on, who is considered almost an entirely supernatural being in human flesh. As Martin Gusinde recalls from his long talks with the Xo’on Tenenesk2, the common Selk’nam didn’t need to worry a great lot about invoking Temáukel’s wrath, as long as they didn’t violate severe taboos. The same applied to Howenhs. They feared those forces, admiring their might, but as Tenenesk stated ”Every one (human) lives their days peacefully, because there’s the subconscious conviction that Temáukel didn’t bother anyone with illness or untimely death as long as they acted according to his precepts”.3 There was also the very reassuring belief that when a ”normal” Selk’nam died, their soul would ascend into the Wintek and beyond, reuniting with Temáukel, up there in the Wintek Sho’on.

There’s not great differences between common tribesmen and outsider humans, cosmology-wise. If anything, what sets them apart is that Selk’nam tend to their local Xo’on (often a relative, as their wandering clans were patrilineal and limited in size), which makes them indirectly gain the favor of the mighty sorcerer, whose alleged powers will be discussed later.

There’s also a curious detail that (tries) to explain why the outsiders look different (as in factions, complexity, height…). As we saw in their creation mythos, Kenos created the first Selk’nam by putting together two genitals made of mud. After the first white men arrived to Tierra de Fuego, they added a little addendum, and stated that white people were created some time later, when Kenos was traveling northwards. This time, however, he did it with beach sand, and didn’t bother to stop and teach them how to live their lifes, which explains the different skin tone and culture.

Lastly, it appears modern humans are descendants of some of the first Howenh. As we stated in a previous entry, Howenh looked humanlike once. Their descendants were fellow Howenh for a while, but at some point only humans were birthed from their unions. It’s likely that when Kwányip broke the rejuvenating bath device he also made impossible for new Howenh to appear, as after the latest of them ”died5” of old age, no more appeared.

We can’t say much more about humans in the grand scheme of things. Their customs and way of seeing the world is an inseparable part of their identity, but that’s for another entry.

Xo’on

The Selk’nam clans consisted mostly of average people, who lived as semi-nomads for the most part and had not many fears or worries in their mundane routines (well, while they were left alone by the rest of the world, that is). There’s an exception to this placid existence, however, and comes in the form of the dreaded shamans, the Xo’on!

Xo’on were a very exclusive groups among the Selk’nam. Most of the time, only one or two were present in each Selk’nam haruwen6, and they had a very prestigious reputation in their small community. Despite that, they weren’t detached of their community, and often helped with their tribe’s particular goals, whatever they would be at the moment.

To the left, a picture of the aforementioned Tenenesk, a seasoned Xo’on of mixed ancestry (Selk’nam-Haush), wearing traditional makeup for a very special occasion, the celebration of the Hain ceremony. Likely taken by his friend Lucas Bridges7 in the early 1920s. Do notice his mustache, a sign of the europeization he and other few surviving Selk’nam went through by the end of XIX century.

Despite his menacing role as a Xo’on, Tenenesk was consistently described as an easy-going and overall reasonable individual.

Xo’on powers were very varied, and their extent is left somewhat ambiguous. They claimed to be able to send death and illness to rival tribesmen, and even to outsider groups of people. To do so, they would enter a state of profound trance by chanting to themselves for hours. The time could greatly vary, with some of the most experienced ones managing to do it in under an hour; they claimed to be able to eventually harness this hazardous abilities, projecting them on their enemies.

Selk’nam believed that most (if not all) unnatural causes of death among their people were the fruit of a Xo’on, who used their magic to provoke indirect demise (for example, they stated that if someone was killed in combat by being shot by arrows, that was thanks to a rival Xo’on, whose chants directed them to a target beyond it’s vision). This also applied to diseases and accidental deaths, in short, anyone who ended up dead abruptly.

That’s not to say all their abilities were of destruction and doom. Not at all! Many Xo’on also claimed to have healing powers and the ability to protect their kin from magic and misfortune, either by blessing them in combat, or by trying to remove diseases and speed the healing of an injured body. This set of abilities also came with their own chants, and likely depended of external circumstances, too. A Xo’on could be more specialized in nurturing or destructive skills, but apparently they were expected to be at least well-versed in both categories.

Furthermore, not even the word ”Xo’on” has an inherently bad meaning, or one associated with destruction or death by itself. Xo’on appears to have meant something akin to ”healer”, if we compare it with the word for a (white) doctor, Koliot-Xo’on8.

Xo’on powers were bound to other factors outside their control, such as the weather, or how focused and spiritually replenished they felt at the time. Even the most seasoned ones would see their perceived abilities fluctuate a lot due to different reasons. For example, Tenenesk mentioned he relied a lot on the moon (Kre)10, and her will determined whether he could perform at full power or not.11

Finally, they seemed to apply specific painting on their faces for their Xo’on duties, using other color combinations and arrangements for less otherwordly situations12.

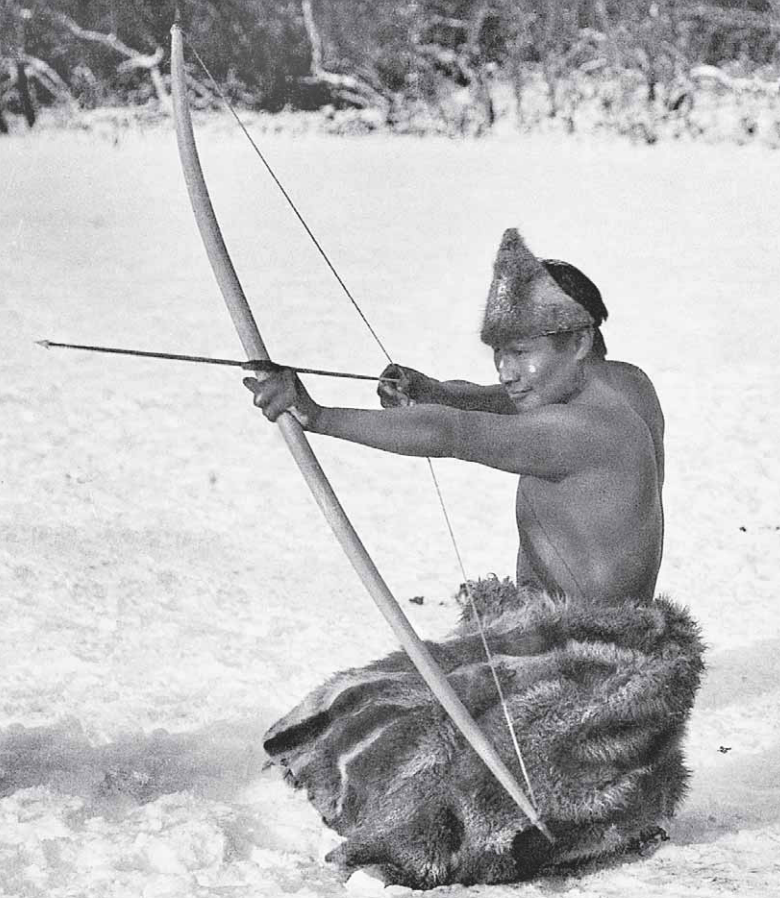

The Xo’on shown on the right side is the same one from the previous images. Here he’s putting paint make up before healing the other felled Selk’nam.

His name was Pachiek (lit. Broad Haunch).

Controversies

Now, regardless of what use they gave to their powers, the very existence of a Xo’on was a taboo to Selk’nam beliefs. The power of life, and specially death, is one that belonged specifically to Temáukel, the one and only true god of their pantheon. It was him the only one who had the legitimate right to kill with his willpower, because he was the one who made all the life that existed (by using Kenos).

A human attaining this power was borderline contradictory, as they had no legitimacy to have such divine tools on their hands. By all accounts, a Selk’nam that was zealous and aware of his world views should have opposed raising a Xo’on… yet, no one ever questioned their existence.

It’s a very strange phenomenon that Gusinde noticed, and asked Tenenesk about it. The later acknowledged the issue at hand, meaning that they are self aware about it. He hand waved it away, however, and just stated that Selk’nam live with that contradiction and they just ”don’t think too much about it”13. After all, having someone with that toolkit is convenient, specially so when there’s one or two in every neighboring Haruwen!

How to become a Xo’on

The Xo’on always made sure to get at least one younger pupil to teach them the ways of the Xo’on, to take the mantle after the former. Even though the vast majority were men, it seems women could also become one. Tenenesk’s first wife, Leluwhachin, was the only fully fledged, female Xo’on registered in written records. Could other women have been Xo’on previously, forgotten far before they would formally go down in history? We may never know. There’s also the case of Lola Kiepja, who was a Xo’on in training until the tragedy of the Selk’nam genocide reached her Haruwen, which put an abrupt end to her tuition14. In 1963 and being about 90 years old, she was recorded by the anthropologist Anne Chapman, registering many traditional chants to posterity (can be listened here).

Going back to the training, it lasted for years, and the apprentice kept honing their ability to memorize chants and focus mentally even after they had learnt everything the Xo’on could teach, only ending when the later eventually died (whatever the cause would be).

At that point, the soul of the Xo’on, called waiuwin15 would leave their body. But, unlike common Selk’nam souls, it would not reach Wintek. Instead, it would possess the apprentice, turning them into the new shaman. This way, the waiuwin stayed connected and nurturing itself with the knowledge of passing generations, inhabiting it’s new vessel. Only then, the powers of the apprentice would be unlocked, as now the waiuwin would let them freely channel them under the right circumstances.

Gusinde writes that the chant ritual felt like entering into a profound dream, with the waiuwin taking control of their actions and making them move almost automatically. Like some sort of astral projection, they felt the spirit detaching from the body and could see through it, visiting the moon to try and talk with her.

Speaking of becoming a Xo’on, it comes with a serious disadvantage: the waiuwin, as we stated, could never travel to Wintek, possibly due to it’s defiance to Temáukel (true reasons are unknown). Tenenesk said ”We don’t know how Xo’on act. If they kill a man, we don’t know how they deal with Temáukel, as they never negotiate with him [when using their magic]”.16 This meant they were forbidden from ever getting the liberation that their peers obtained, being bound to the lowly world forever.

Kash-waiuwin-Jir

A very rare and special occupation of the Selk’nam was the long awaited Kash-waiuwin-Jir (lit ”Internalization of the waiuwin by singing”). This very rare competition took place in southernmost part of Tierra de Fuego (close to or in the Haush territory, with Lola Kiepja believing it was actually invented by them), where Selk’nam from all the island would reunite to barter and go through friendly contests (there were also sportive trials for the hunters). It’s assumed during those occasions all the Selk’nam ceased all hostilities related to trespassing neighboring Haruwen to get there.

Kash-waiuwin-Jir was a contest made for shamans, were they would sing for hours and try to prove how strong their trance was, for example, by walking over burning coal without flinching!17 This way they could show the spectators how powerful their waiuwin possession was while not hurting or killing any of them. That’s how they decided who was the most powerful shaman of them all at the time. This celebration is not very documented (I haven’t been able to find photos picturing it, as of now at least). It’s possible that the natives (Haush and Selk’nam) stopped doing it as the colonization of their lands pushed them away and caused distress and war among them as their shelter and resources were quickly taken away.

This is most of the relevant information I found about the Xo’on topic. There’s possibly even more worth mentioning, and for that I recommend diving into the sources I used, both in previous articles and in this one. In following entries we will talk about other anthropological aspects, other Howenh tales, and eventually about crucial traditions of this people, such as the already mentioned H’ain. I hope the next entry doesn’t take as much time to bring out… until then!

Sources I consulted18:

- Gusinde, M. (1931), Die Feuerland-Indianer I. Band Die Selk’nam, Modling bei Wien

- Agostini, A. (1910), La patagonia en el año 1910. Unknown publisher (Self-published?) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=copSpkomriU

- Bridges, E. L. (1948), Uttermost Part of the Earth, E. P. Dunton

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/haush/cosmologia.html

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/selknam/territorios.html

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/biografias/tenenesk.html

- Chapman, Anne. (1972), Selk’nam (Ona) Chants of Tierra del Fuego. Folkways Records (both the written addendum and the album itself used as the source). Album listenable here: https://youtu.be/JjuE4LEsolE

- Fun fact: Apparently I miswrote them as ”HoweHN” in all my previous articles… Just corrected it. ↩︎

- Gusinde, M. El mundo espiritual de los Selk’nam, published in 1931 by Zeitschrift Anthropos ↩︎

- Gusinde, p. 52 ↩︎

- Snapshot taken from Agostini’s documentary ”La patagonia en el año 1910”, viewable here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=copSpkomriU ↩︎

- That is, ascended into new beings ↩︎

- The name of a territory that belonged to an specific Selk’nam clan. We’ll talk more about them when we properly their society and way of living. ↩︎

- As one of the last Xo’on that ever existed, Tenenesk was friends with several European anthropologists and interviewed and documented by several of them. Nearly all works from late XIX century to the early 1920s regarding Selk’nam cosmology have been doable thanks to his collaboration. ↩︎

- In the agglutinative Selk’nam language Koliot is a word that describes things originating from the Europeans or just the white, outsider ethnicities. For example, Koliot-kwakl meant ”white’s disease”, refering to the deathly smallpox epidemic that killed so many of the remaining tribesmen. ↩︎

- Also from Agostini’s work. ↩︎

- Bridges Edward, Lucas. Uttermost Part of the Earth, published in 1948 by E. P. Dunton in New York, pp. 261-262 ↩︎

- Do notice that in this specific conversation Bridges was more or less teasing Tenenesk (in a friendly way) about his powers being fake and daring the former to try and curse him, to no apparent effect. This means Tenenesk could have felt disheartened or was making excuses at the moment, not reflecting his true beliefs to their total extent. For what is worth, Lola Kiepja would later confirm in one of her chants that the moon and the spirit of a Xo’on had a meeting during the trance. ↩︎

- Selk’nam people seemed to value painting make-up in great regard, using it in numerous contexts and for a wide variety of reasons, their styles and (mostly informal) rules of aesthetics varying depending of the Haruwen. ↩︎

- Gusinde, p. 55 ↩︎

- Chapman, Anne. Selk’nam (Ona) Chants of Tierra del Fuego, published in 1972 by Folkways Records in Argentina. She claimed to have healing powers, but not destructive ones. ↩︎

- This name is given specifically to the soul of a Xo’on. ↩︎

- Gusinde, p. 55 ↩︎

- Gusinde, M. Die Feuerland-Indianer I. Band Die Selk’nam, also published in 1931, by Modling bei Wien. pp 146-148. ↩︎

- On top of the ones from previous, related article(s) ↩︎

Post your thoughts!