We have already discussed a great deal of Selk’nam tenets, looking back! There’s still a lot to talk over if we want to fully understand how they viewed the world, and their own kin. Today, we will talk about how their society organized, but specially about how they viewed and treated both genders, and even the reasons they gave towards following their own status quo from a mythological perspective. It’s a very important aspect within their culture, that will also help in making future articles easier to understand. Let’s get started!

Societal distribution and demography

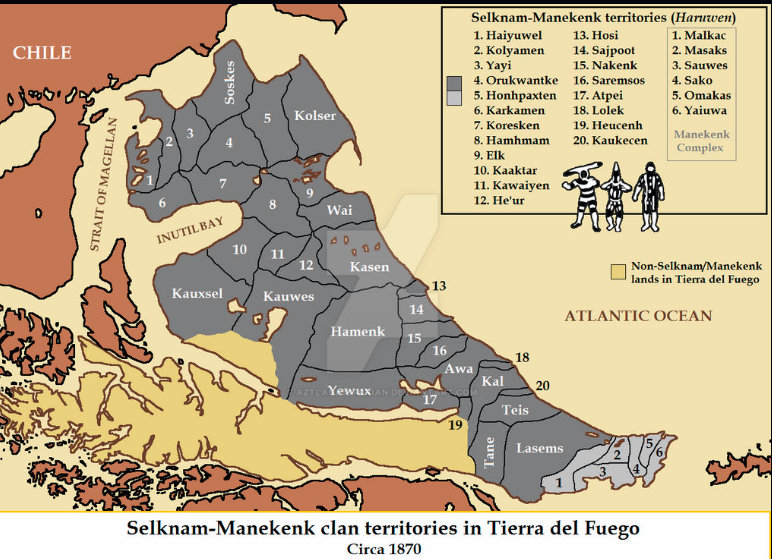

As per the case of most cultures and civilizations across the world, the Selk’nam lived under a profound patriarchy. As we mentioned before, their clans were patrilineal; meaning, every clan could trace it’s origins to a single male ancestor. On top of that, they were patrilocal, meaning each clan would roam through the same land that male figure chose generations back (what they called the Haruwen), giving them their semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Allegedly, between 30 and 80 Selk’nam clans thrived across Isla Grande1, along with 6 Haush ones in the southeastern peninsula2. Their population was low, and very stable. In the whole Isla Grande, a territory bigger than Belgium, figures of up to 5000 Selk’nam have been proposed3 at their peak.

Inside a Haruwen, the Selk’nam would wander chasing guanacos, harvesting fruits or fishing. For weeks or even months they would stay and carry on their lifestyle in a single specific point, putting up tents and cabins and making campfires.

The lighter cabins would be dismantled and transported during their occasional movements.

To the right, the previously mentioned Tenenesk with his second wife and their child, posing in front of a wooden cabin. The photo was taken by Martin Gusinde at some point in the early 1920s.

Clans endured harsh living conditions. During the winter, temperatures dropped below freezing point, and the warmer months hardly went over 10 ºC (50 ºF). Their sources of food also decreased, making survival challenging for smaller or uncoordinated groups. After all, Tierra del Fuego island is less than 500 miles away from the Antarctic continent!

Haruwen were highly respected by their inhabitants as their legitimate territory to exploit. That meant trespassers would often be met with open hostility, even if they were fellow Selk’nam from a neighboring Haruwen. This explains why a substantial percentage of the Selk’nam that died during their genocide were killed by other members of their own culture; as they were pushed away by the better armed Europeans, most had no other options than migrate into already crowded and threatened Haruwen, and their only odds to survive were to fight for resources against other clans.

To the right, a colorized Haruwen map made by Gusinde and Streit. The Haruwen number fluctuated wildly, which explains why this particular iteration only numbered about 30 of them. This colorized version has been spotted on Punta Arenas Facebook group and can be visited by clicking here4.

In peaceful times, though, the clans would meet and enter other Haruwen in certain occasions. Those could be festive (like the Kash-waiuwin-Jir), or for practical purposes, such as marriage arrangements. When a Selk’nam woman was married into a different clan, she and her children would now belong to the later one, but they were expected to have cordial relations with the mother’s former clan, too. Also, a widowed woman’s children could either live in the mother or the father clan, and be accepted in either one (assuming the mother came from a different lineage).

Lastly, clans and Haruwen weren’t, of course, expected to stay the same way forever. Over time, their numbers would slowly increase, differences could set them apart, and even in such a big territory scarcity played a role, with their prey drifting around and chasing the pastures. Those conflicts didn’t necessarily end violently: a disgruntled (male) Selk’nam and his family (wive[s]5 and children) were free to leave, dividing the Haruwen in two after settling the boundaries of both groups. This was beneficial for the original clan, too, as it meant less mouths to feed in difficult periods.

Gender roles

While life was harsh for all the Selk’nam, women seemed to get the short end of the stick in most of the occasions. Save for hunting, Xo’on obligations and the occasional battle6, women would perform most of the duties of the Haruwen, including carrying the materials of the smaller tents on their backs, the spare guanaco fur robes, and their own babies. Those movements would become more common during the winter, when it was mandatory to keep track of the dwindling prey, walking for hours amidst the cold while wielding great weights.7 While they were settled, they would also gather edible plants and berries, and overall try to help the community in any way they could or were ordered to.

The few families that constituted each clan decided altogether their next courses of action. Usually there was no hierarchy involved, but considering the patriarchal nature of their communities, it’s likely that women proposals had less weight in their discussions.

Spiritually-wise, the Selk’nam had a very interesting way of enforcing the place each role had in the world: during certain ceremonies (such as the Hain), they would dress themselves as certain specific spirits8 (not to be confused with the Howenh)9, and then run around the campfires and tents, in order to scare the women and children with their otherworldly aspect. Anne Chapman recalls they would sometimes harass women deemed as unsubmissive, rebellious or adulterous10, mostly by shoving them around and toppling down their tents (quite annoying, but at least those were light and portable, so not very difficult to rebuild).

Apparently, the idea was that women would be utterly terrified of disobeying the patriarchy, under the idea that spirits would hound and attack them, and thus the status quo would firmly stay… but the reality is a little bit different.

As Lola Kiepja said (and every bit of evidence points to it being that way across most if not all Haruwen), women actually knew all along who the men behind those costumes were. They were fully aware that those fearsome spirits did not exist, or at least the ones that chased them weren’t the real deal. But since the children didn’t know (and it was imperative that it stayed that way until their adulthood) and they were expected to be scared and follow their husbands’ command, they more or less played along. So, to summarize, both of them pretty much played the part while thinking they were tricking the other gender. All a performance, their fear included!

Despite the oppressive nature of this custom, Kiepja stated most women had a fun time seeing all those theatrics unfold. It’s likely that they simply took it as an opportunity to laugh at their husbands occurrences and as a way to release some stress.

Even the men took some of the rites as a comedy; for example, other of their performances featured Koshménk, a spirit known basically for being a cuckold (married to the lustful Kulan). He would be represented by four Selk’nam, each dressed as one of his manifestations11, and run around the village asking about his wife with great exasperation, something that often made the women laugh audibly12.

To the right, a photo of two Koshménk performers. Their ceremony involved a lot of physical action (that will be further explained in the right article), and they had to constantly hold their pointy masks with their hands so they didn’t slip).

In short, it seems the Selk’nam used religious imagery and customs to make sure their societal configuration and gender expectations stayed the same over generations, even if the female natives knew more than they told them. It’s a very interesting way of projecting their values to the rest of the tribe; instead of merely relying on the force of habit and ingrained social cues, they used a very explicit and elaborated corpus of spirits, each with it’s own name, design, personality… to give credibility to their claims and legitimate their reason on forces greater than them.

The religious explanation

As we discussed in the previous entry, the Selk’nam were surprisingly self aware of their beliefs, contradictions and ways of life. But unlike the Xo’on case, were they simply ”didn’t think much about it”, they did form a mythological explanation of the patriarchy, an intriguing story involving Howenh, violence and betrayal that Martin Gusinde recorded from Tenenesk recalls, that we will summarize now. This story features Kren and Kre, the sun and the moon, respectively, and happens after Čénuke left and death became permanent for those that suffered it, but before the last of the Howenh died and/or transformed into new beings or forces of nature13.

Kren was the son of Kranakhátaix, the old sun and one of the first beings to become an aspect of nature14, who shone with such intensity that days were almost uninterrupted by the night. Eventually he would grew weaker and tired, and by the time this tale took place, he was almost too exhausted to keep up with his role15. At this point, Kren and Kre were already married and had a daughter together, the so called beautiful16 Tamtam.

The society the Howenh formed was the polar opposite of that of the ”modern” Selk’nam: female Howenh ruled over their men and made them do most of the meaningful work, in some form of strict matriarchy. Even the most powerful males (like Ko’oh, current Howenh incarnation of the sea) bent over their wishes and complied, never rejecting their place in that world. Why? Due to the Hain celebration.

The old Hain

Up to recent times Selk’nam human tribesmen (emphasis on the ”men” part) celebrated the Hain, the adulthood passage whose truth only men knew about. The old Hain that Howenh partook in worked the same way, except it was the women who disguised themselves and scared the male Howenh, chasing them as far as they could run. Contrary to the modern, human women, the ancient male Howenh did believe the ghastly creatures were real, and they instilled mortal fear on them. Females were experts in this craft, and for a long time their husbands and fathers believed it, as no one of them ever had any reason to reveal it. That, of course, includes Kren, oblivious to the truth as all the other adult males. The tradition would have held up forever, and eventually, when the last Howenh left, humans would have taken and perpetuated it the same way, but an unfortunate incident undid all of this: the lie was revealed during one of the Hain.

While one of the women was still behind a cabin dressing up as one of the sinister spirits, she was spotted by three sneaky male Howenh: Sit, Kehke and Chechu, who immediately realized what was truly going on. Before she could intercept them or do anything, they ran away, screaming everywhere the news about the scam the women pulled. The would scream so much and so loudly, that even after their death/ascension they became loud birds, respectively the Oystercatcher, a unidentified one called ”Borotero17” and the Andean Sparrow.

Massacre and regret

When the news reached Kren, he became furious over having been tricked for so long. In a fit of rage he beat and threw his wife Kre onto the campfire of their place to kill her. She miraculously escaped by leaving the world of the mortals and becoming the moon. Kren was still angry at her, and thus turned into the current sun, displacing his old and powerful father, to keep his pursue and eventually kill her. That’s why, according to the Selk’nam, the moon has it’s dark grey spots (what we call lunar mare): they’re the burn marks the poor, disfigured Kre still bears to this day, still fleeing of her husband’s wrath.

Before resuming his chase, Kren also spearheaded the murder of all adult Howenh women, for they knew and perpetuated this secret18. This included even his own daughter, Tamtam! No one was spared in what we could only define as a genuine Gendercide. Even the wives of the three whistle-blowers were killed, despite their attempts to prevent it. Only the children were spared, as they weren’t initiated in the Hain yet, and took no part in the schemes. Kre was thus the only adult female Howehn that was not killed, even if she ended ascending as all of them do after death anyways.

After their rage faded, the male Howenh realized the evil of their act, and took penitence by journeying along with the children to the east, facing the most sacred Sho’on of Wintek and going beyond the land and even the seas (likely the Selk’nam meant they went so far they crossed even the southern Atlantic Ocean, possibly to the very end of the physical world as they understood and imagined it), and they remained there for centuries, as they were beings of a far larger lifespan even before ascending. All that time they wept, remembering their mothers, wives and sisters, all killed mercilessly over a scheme. And only after such a long time, they returned to Tierra de Fuego. By then, the little girls had already grown into adults, and were ready to return home. And so they did19.

As a last measure, the male Howenh decided from now on, they would be the ones to call the shots, and in an ironic twist of fate, decided to reinstate the Hain. Only this time, they would be the ones to partake on it, and scare and coerce women with the threat of spirits and monsters of all kind under the threat. The roles reversed to the exact opposite, and ever since, and long past the age of Howenh, when the last of their kin transformed, they kept doing the same rites of initiation.

Back to the Age of Mortals

For millennia, the rigid societal roles of men and women were enforced by the Selk’nam. They likely existed way before the Selk’nam appeared as an independent group, probably predating even the archaic peoples they, the Haush and the Tehuelche came from altogether. The Selk’nam, trying to find a reason to explain why their society was that way, came at some point with the idea of the Hain, formed while their mythology was on it’s early stages.

It’s not an exaggeration to imagine they kept this way of being for countless centuries, not so long after they ended on Tierra de Fuego and started being their own people. Who knows when, exactly? When did the gender inequality start? Was the mythological explanation ever the same? What was the first version, how has it evolved as new generations kept hearing and recalling it, again and again?

Again, it’s worth wondering if this inequality could have lasted forever. It is known that female Xo’on, the most respected position within Selk’nam peoples, existed and practiced their duties successfully. Was this sporadic presence of powerful women a byproduct of western influences? Or did it happen long before the Europeans arrived?

Those are questions that are not for us to answer, but for anthropologists and professionals to ponder and research about, and only the future will tell if we can shed more light on the distant past of the Selk’nam, even more mysterious than their fleeting last decades.

And this is a summary of most of the things we can say about this topic on the Selk’nam. Considering how little bibliography there is left about such matters (and how contradictory what little we have left to contrast) there is a fair amount of information to digest. Next time we will keep exploring more spiritual aspects of the Selk’nam, maybe other spiritual creatures apart of the Howehn, or even the Hain itself, since we have alluded to it several times, and I have yet to write an article about it. I think it will help in hindsight to take care of that one, so every previous entry that talks about it is finally properly understood. Who knows, who knows… one way or another, until then!

Sources I consulted20:

- https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/las12/13-989-2004-01-30.html

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/selknam/koshmenk.html

- Chapman, Anne. (2010), European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin. Cambridge University.

- Chapman, Anne. (1990), End of a World: The Selknam of Tierra del Fuego. Zagier & Urruty Pubns

- The specific Island of Tierra de Fuego that Selk’nam inhabited ↩︎

- And Yaghan people in the southernmost side, who also stretched across smaller islands and islets of Chile and Argentina. Unlike Selk’nam, they were able to move across the archipelago with the use of canoes, there’s even theories that they were the ones that helped Haush and Selk’nam reach Isla Grande hundreds of years back, since they didn’t have any grasp of navigation technology. ↩︎

- Chapman, Anne, European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (2010) ↩︎

- The original image is a hundred years old, free from copyright laws. This image is just a recolor of the aforementioned one, therefore it’s still free from copyright issues. ↩︎

- Selk’nam were monogamous most of the time, but were not against polygamy, sometimes having more than one wife at once and multiple children with each one. ↩︎

- And even then, them being on the losing side during a confrontation between clans, or the genocide itself, didn’t spare them from being involved in conflict ↩︎

- Lola Kiepja would tell Anne Chapman, as per the later testimony, that walking in the cold was one of the worst parts of the Selk’nam lifestyle, still remembering the pain on her naked palms decades later ↩︎

- Which had their own, particular names, but not a term to define all of them altogether, which is why I will just call them spirits, as Gusinde or Chapman did. Sometimes they’re called ”Klóteken spirits” by Gusinde, but we won’t use those term here, since Klóteken is a term that can only be applied in the modern Hain. ↩︎

- In following articles more about these figures will be explained. ↩︎

- Extracted from Anne Chapman’s interview in 2004 in https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/las12/13-989-2004-01-30.html (Near the end of the article) ↩︎

- Basically different aspects of the same being. This is an idea that exists across many cultures of our world. For readers familiarized with Christianity, imagine the holy trinity as a somewhat similar idea. ↩︎

- https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/patagonia/selknam/koshmenk.html The women felt so unthreatened by Koshmenk not only they laughed, but even received his manifestations by singing. This reinforces the idea that they all knew the reality of Hain and spirits, but complied as to respect the old tradition. ↩︎

- I can’t recommend enough to read the linked article, otherwise mentiones of mythological chronology and related events may get a little difficult to understand ↩︎

- The creation myth mentions the existence of day and night even before death existed and Howenh started morphing into animals and natural aspects. This would make the existence of the day and night cycle impossible, as Kranakhátaix couldn’t have ascended yet. One possible explanation is that Kenos turned him that way long before death was established, turning him into an exceptional case of early ascension. ↩︎

- There is no indicative the Selk’nam age once they have transformed, maybe he grew spent from shining with all his might over such a long time. ↩︎

- A title given to her according to Anne Chapman’s work End of a World: The Selknam of Tierra del Fuego (1990), p. 106 ↩︎

- Originally mentioned, again,in Chapman’s End of a World: The Selknam of Tierra del Fuego. I personally researched avian species in Tierra de Fuego, but none with a similar name showed up in the results. It’s not a native Selk’nam word either (they didn’t have some of the phonemes of that word in their language). Could it be a forgotten archaism to depict a different bird? Further research is required. ↩︎

- Of course, being Howenh the women didn’t die permanently and eventually transformed into aspects of nature, for example Tamtam became the first canary after her death. But it’s strongly implied once they became part of the nature they stopped communicating altogether with the humanoid Howenh, detaching entirely from society. ↩︎

- This recount of the events comes from Anne Chapman, and also operates on a different timetable: It states the humans were created ONLY after the last Howenh died out, implying that Kenos stayed on earth for a longer time than the version we used for our second article, where he leaves at some point after creating the humans while there’s still most of the Howenh around. Both versions have a series of events that are contradictory and nearly impossible to reconcile, but the tale of Kre and Kren can, for the most part, be successfully implemented in our chosen version, and all the Selk’nam agree for the most part about the events that happened. The major divergence comes around death: Martin Gusinde version says death arrived after Kwanyip broke the cycle with his magic to help his brother, while Anne Chapman’s says the male Howenh journey ”brought it from the north”. Aside of this last part, which we will ignore to avoid further confusion, everything else tracks with what we have analyzed until now. ↩︎

- On top of the ones from previous, related article(s) ↩︎

Post your thoughts!